What is a research paper abstract?

Research paper abstracts summarize your study quickly and succinctly to journal editors and researchers and prompt them to read further. But with the ubiquity of online publication databases, writing a compelling abstract is even more important today than it was in the days of bound paper manuscripts.

Abstracts exist to “sell” your work, and they could thus be compared to the “executive summary” of a business resume: an official briefing on what is most important about your research. Or the “gist” of your research. With the majority of academic transactions being conducted online, this means that you have even less time to impress readers–and increased competition in terms of other abstracts out there to read.

The APCI (Academic Publishing and Conferences International) notes that there are 12 questions or “points” considered in the selection process for journals and conferences and stresses the importance of having an abstract that ticks all of these boxes. Because it is often the ONLY chance you have to convince readers to keep reading, it is important that you spend time and energy crafting an abstract that faithfully represents the central parts of your study and captivates your audience.

With that in mind, follow these suggestions when structuring and writing your abstract, and learn how exactly to put these ideas into a solid abstract that will captivate your target readers.

Before Writing Your Abstract

How long should an abstract be?

All abstracts are written with the same essential objective: to give a summary of your study. But there are two basic styles of abstract: descriptive and informative. Here is a brief delineation of the two:

| Descriptive abstract | Around 100-200 words (or shorter) in length; indicates the type of information found in the paper; briefly explains the background, purpose, and objective of the paper but omits the results, often the methods, and sometimes also the conclusion |

| Informative abstracts | One paragraph to one page in length; a truncated version of your paper that summarizes every aspect of the study, including the results; acts as a “surrogate” for the research itself, standing in for the larger paper |

Of the two types of abstracts, informative abstracts are much more common, and they are widely used for submission to journals and conferences. Informative abstracts apply to lengthier and more technical research and are common in the sciences, engineering, and psychology, while descriptive abstracts are more likely used in humanities and social science papers. The best method of determining which abstract type you need to use is to follow the instructions for journal submissions and to read as many other published articles in those journals as possible.

Research Abstract Guidelines and Requirements

As any article about research writing will tell you, authors must always closely follow the specific guidelines and requirements indicated in the Guide for Authors section of their target journal’s website. The same kind of adherence to conventions should be applied to journal publications, for consideration at a conference, and even when completing a class assignment.

Each publisher has particular demands when it comes to formatting and structure. Here are some common questions addressed in the journal guidelines:

- Is there a maximum or minimum word/character length?

- What are the style and formatting requirements?

- What is the appropriate abstract type?

- Are there any specific content or organization rules that apply?

There are of course other rules to consider when composing a research paper abstract. But if you follow the stated rules the first time you submit your manuscript, you can avoid your work being thrown in the “circular file” right off the bat.

Identify Your Target Readership

The main purpose of your abstract is to lead researchers to the full text of your research paper. In scientific journals, abstracts let readers decide whether the research discussed is relevant to their own interests or study. Abstracts also help readers understand your main argument quickly. Consider these questions as you write your abstract:

- Are other academics in your field the main target of your study?

- Will your study perhaps be useful to members of the general public?

- Do your study results include the wider implications presented in the abstract?

Outlining and Writing Your Abstract

What to include in an abstract

Just as your research paper title should cover as much ground as possible in a few short words, your abstract must cover all parts of your study in order to fully explain your paper and research. Because it must accomplish this task in the space of only a few hundred words, it is important not to include ambiguous references or phrases that will confuse the reader or mislead them about the content and objectives of your research. Follow these dos and don’ts when it comes to what kind of writing to include:

- Avoid acronyms or abbreviations since these will need to be explained in order to make sense to the reader, which takes up valuable abstract space. Instead, explain these terms in the Introduction section of the main text.

- Only use references to people or other works if they are well-known. Otherwise, avoid referencing anything outside of your study in the abstract.

- Never include tables, figures, sources, or long quotations in your abstract; you will have plenty of time to present and refer to these in the body of your paper.

Use keywords in your abstract to focus your topic

A vital search tool is the research paper keywords section, which lists the most relevant terms directly underneath the abstract. Think of these keywords as the “tubes” that readers will seek and enter—via queries on databases and search engines—to ultimately land at their destination, which is your paper. Your abstract keywords should thus be words that are commonly used in searches but should also be highly relevant to your work and found in the text of your abstract. Include 5 to 10 important words or short phrases central to your research in both the abstract and the keywords section.

For example, if you are writing a paper on the prevalence of obesity among lower classes that crosses international boundaries, you should include terms like “obesity,” “prevalence,” “international,” “lower classes,” and “cross-cultural.” These are terms that should net a wide array of people interested in your topic of study. Look at our nine rules for choosing keywords for your research paper if you need more input on this.

Research Paper Abstract Structure

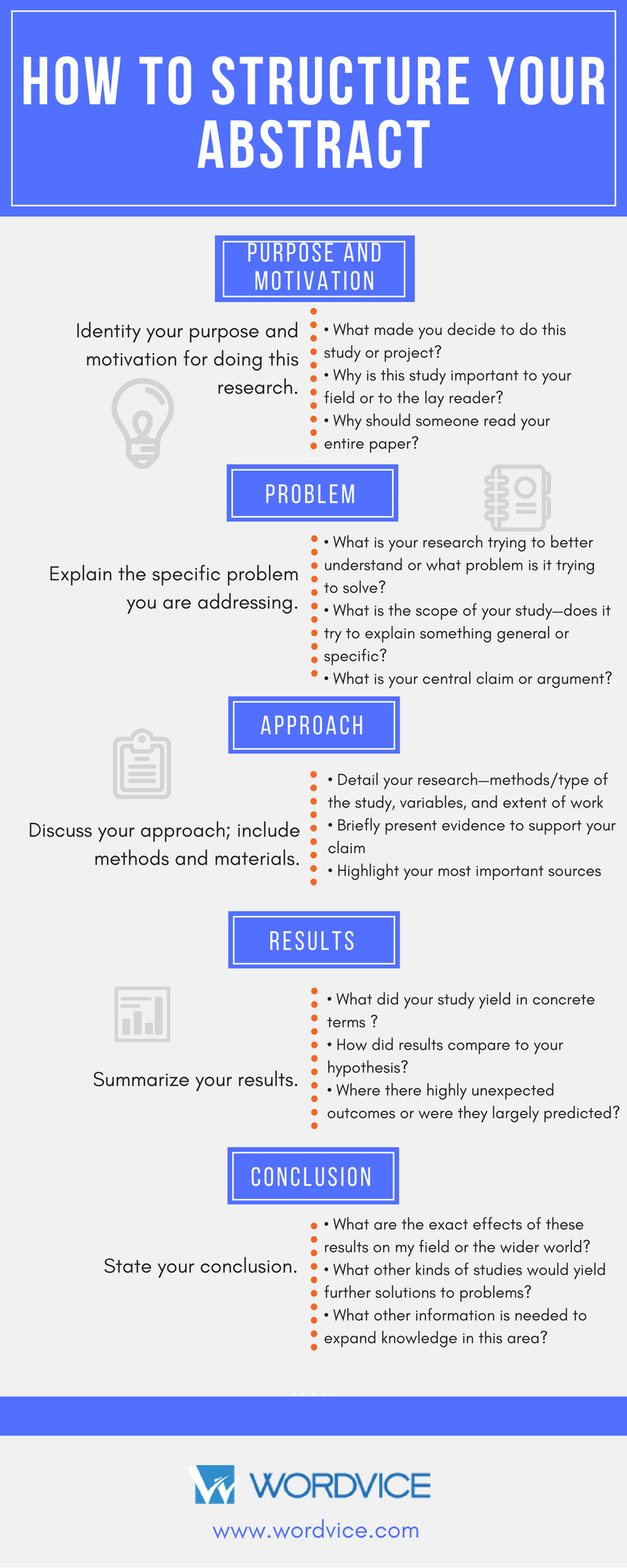

As mentioned above, the abstract (especially the informative abstract) acts as a surrogate or synopsis of your research paper, doing almost as much work as the thousands of words that follow it in the body of the main text. In the hard sciences and most social sciences, the abstract includes the following sections and organizational schema.

Each section is quite compact—only a single sentence or two, although there is room for expansion if one element or statement is particularly interesting or compelling. As the abstract is almost always one long paragraph, the individual sections should naturally merge into one another to create a holistic effect. Use the following as a checklist to ensure that you have included all of the necessary content in your abstract.

1) Identify your purpose and motivation

So your research is about rabies in Brazilian squirrels. Why is this important? You should start your abstract by explaining why people should care about this study—why is it significant to your field and perhaps to the wider world? And what is the exact purpose of your study; what are you trying to achieve? Start by answering the following questions:

- What made you decide to do this study or project?

- Why is this study important to your field or to the lay reader?

- Why should someone read your entire article?

In summary, the first section of your abstract should include the importance of the research and its impact on related research fields or on the wider scientific domain.

2) Explain the research problem you are addressing

Stating the research problem that your study addresses is the corollary to why your specific study is important and necessary. For instance, even if the issue of “rabies in Brazilian squirrels” is important, what is the problem—the “missing piece of the puzzle”—that your study helps resolve?

You can combine the problem with the motivation section, but from a perspective of organization and clarity, it is best to separate the two. Here are some precise questions to address:

- What is your research trying to better understand or what problem is it trying to solve?

- What is the scope of your study—does it try to explain something general or specific?

- What is your central claim or argument?

3) Discuss your research approach

Your specific study approach is detailed in the Methods and Materials section. You have already established the importance of the research, your motivation for studying this issue, and the specific problem your paper addresses. Now you need to discuss how you solved or made progress on this problem—how you conducted your research. If your study includes your own work or that of your team, describe that here. If in your paper you reviewed the work of others, explain this here. Did you use analytic models? A simulation? A double-blind study? A case study? You are basically showing the reader the internal engine of your research machine and how it functioned in the study. Be sure to:

- Detail your research—include methods/type of the study, your variables, and the extent of the work

- Briefly present evidence to support your claim

- Highlight your most important sources

4) Briefly summarize your results

Here you will give an overview of the outcome of your study. Avoid using too many vague qualitative terms (e.g, “very,” “small,” or “tremendous”) and try to use at least some quantitative terms (i.e., percentages, figures, numbers). Save your qualitative language for the conclusion statement. Answer questions like these:

- What did your study yield in concrete terms (e.g., trends, figures, correlation between phenomena)?

- How did your results compare to your hypothesis? Was the study successful?

- Where there any highly unexpected outcomes or were they all largely predicted?

5) State your conclusion

In the last section of your abstract, you will give a statement about the implications and limitations of the study. Be sure to connect this statement closely to your results and not the area of study in general. Are the results of this study going to shake up the scientific world? Will they impact how people see “Brazilian squirrels”? Or are the implications minor? Try not to boast about your study or present its impact as too far-reaching, as researchers and journals will tend to be skeptical of bold claims in scientific papers. Answer one of these questions:

- What are the exact effects of these results on my field? On the wider world?

- What other kind of study would yield further solutions to problems?

- What other information is needed to expand knowledge in this area?

After Completing the First Draft of Your Abstract

Revise your abstract

The abstract, like any piece of academic writing, should be revised before being considered complete. Check it for grammatical and spelling errors and make sure it is formatted properly.

Get feedback from a peer

Getting a fresh set of eyes to review your abstract is a great way to find out whether you’ve summarized your research well. Find a reader who understands research papers but is not an expert in this field or is not affiliated with your study. Ask your reader to summarize what your study is about (including all key points of each section). This should tell you if you have communicated your key points clearly.

In addition to research peers, consider consulting with a professor or even a specialist or generalist writing center consultant about your abstract. Use any resource that helps you see your work from another perspective.

Consider getting professional editing and proofreading

While peer feedback is quite important to ensure the effectiveness of your abstract content, it may be a good idea to find an academic editor to fix mistakes in grammar, spelling, mechanics, style, or formatting. The presence of basic errors in the abstract may not affect your content, but it might dissuade someone from reading your entire study. Wordvice provides English editing services that both correct objective errors and enhance the readability and impact of your work.

Additional Abstract Rules and Guidelines

Write your abstract AFTER completing your paper

Although the abstract goes at the beginning of your manuscript, it does not merely introduce your research topic (that is the job of the title), but rather summarizes your entire paper. Writing the abstract last will ensure that it is complete and consistent with the findings and statements in your paper.

Keep your content in the correct order

Both questions and answers should be organized in a standard and familiar way to make the content easier for readers to absorb. Ideally, it should mimic the overall format of your essay and the classic “introduction,” “body,” and “conclusion” form, even if the parts are not neatly divided as such.

Write the abstract from scratch

Because the abstract is a self-contained piece of writing viewed separately from the body of the paper, you should write it separately as well. Never copy and paste direct quotes from the paper and avoid paraphrasing sentences in the paper. Using new vocabulary and phrases will keep your abstract interesting and free of redundancies while conserving space.

Don’t include too many details in the abstract

Again, the density of your abstract makes it incompatible with including specific points other than possibly names or locations. You can make references to terms, but do not explain or define them in the abstract. Try to strike a balance between being specific to your study and presenting a relatively broad overview of your work.

Wordvice Resources

If you think your abstract is fine now but you need input on abstract writing or require English editing services (including paper editing), then head over to the Wordvice academic resources page, where you will find many more articles, for example on writing the Results, Methods, and Discussion sections of your manuscript, on choosing a title for your paper, or on how to finalize your journal submission with a strong cover letter.